I intended to write this post about an entirely different topic, but then I became distracted by the jewelry I saw in this portrait by Thomas Lawrence. Not one to be able to resist a good sidetrack in my historical research, I followed my urge to find out more about the jewelry that was made during the Georgian era.

I intended to write this post about an entirely different topic, but then I became distracted by the jewelry I saw in this portrait by Thomas Lawrence. Not one to be able to resist a good sidetrack in my historical research, I followed my urge to find out more about the jewelry that was made during the Georgian era.

The Georgian era is defined as the years between 1714 and 1830. We need to remember that back then, jewelry was crafted by hand. Due to the lack of precision cutting machinery, precious stones cut during the Georgian era have a rougher look than stones cut today. These stones were set low into the metal and backed with silver, gold, or colored foil behind them to enhance the color and reflect more light through the stone. Silver was the only white metal used for setting diamonds. White gold didn’t come into use until after about 1925, platinum after about 1890.

Throughout the Georgian era, diamonds were the stone of choice. Rock crystal and colored stones such as pink topaz, green chrysoberyl, and purple amethyst were popular early on.

Pearls were fashionable, set alone or mixed with gemstones, and as the years went on emeralds, garnets, rubies, yellow topaz, onyx, coral, and turquoise came into favor as well.

It may surprise some people to hear that fake stones were also used. These stones were known as paste. Paste is faceted leaded glass cut to resemble gems. It is sometimes called “strass” after the 18th century Parisian jeweler, Georges Frederic Strass who became world famous for his paste jewelry which was even prized by the likes of Marie Antoinette. The earrings from my collection and the earrings below are made of paste. They are day/night earrings. This style of earring was developed during the 18th century. Typically this is a two element earring in which the top cluster can be worn separately from the attached drop, making it a more appropriate choice for daytime wear.

During the day, women wore very little jewelry. In many instances you can see portraits of women wearing a simple black ribbon around their neck.

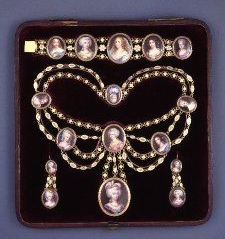

Evenings for the aristocratic set, were an entirely different matter. Short necklaces were prefered and some of the most desirable styles included the dog collar, now known as a choker, and rivieres. A riviere is a necklace with individually set stones of the same size or graduating to a larger size in the front. It could be worn alone or with a pendant attached. Often a riviere was part of a parure, which is a suite or set of matching jewelry including a necklace, earrings, bracelet, and brooch.

The girandole was also popular and used in pendants, brooches, and earrings. This design is composed of three hanging pendants that are set with single or multiple stones hanging from a centerpiece. Georgian girandole jewelry were often embellished with bows, foliate motifs and/or garlands. The popularity of this style began to wan around 1790 as neoclassicism began to dominate the styles of the era.

As the 19th century approached and we move into the Regency era, dress styles changed dramatically and women began to favor delicate empire waist dresses with short sleeves and low necklines. This style of dress was inspired by Europe’s fascination with ancient Greek and Roman culture. Like the style of dresses, the style of jewelry followed suit. Armlets were worn on the upper arms and could be used as a garter to hold up a woman’s glove.

Gold chain esclavage necklaces were part of this neoclassical movement and were worn with drop earrings. These necklaces are comprised of several rows of chains, beads or jewels. In the portrait I was studying, the sitter is wearing an esclavage of pearls.

A simpler style of jewelry also complimented the style of Regency era dresses. If your economic condition did not allow for costly pieces, you could adorn yourself with a simple gold chain and a small pendant.

And finally, this was the era that introduced us to one of my favorite pieces of jewelry: the lover’s eyes. The eye miniature set into jewelry is believed to have originated with the Prince of Wales (later George IV) and his secret wife, Maria Fitzherbert. Their relationship was frowned upon by court, so a miniaturist was employed to paint only the eye and thereby preserve anonymity and decorum. The couple married in 1785, though all present knew the marriage was invalid by the Royal Marriages Act, since George III had not approved. It is believed that Maria’s eye miniature was worn by George IV, hidden under his lapel from the time of their courtship. Apparently George’s lover’s eye must not have been much of a secret since this supposedly led to the lover’s eye becoming fashionable between 1790 and the 1820s.

If you lived in London during the Georgian era and were in the market to purchase something lovely to wear to the opera or to a ball, you could have visited these fine establishments for your jewelry:

- Rundell and Bridge at 32 Ludgate Hill (Rundell, Bridge & Rundell after 1805)

- Phillip’s on Bond Street

- Thomas Gray’s on Sackville Street

- Stedman and Vardon at 36 New Bond Street

Sadly, a large majority of Georgian jewelry has not survived to the present. Many families restyled the pieces to keep up with trends, or they sold them off and the components were taken apart for their value. Brooches and rings are the most common types of Georgian era jewelry still in existence. Earrings and necklaces remain available to a lesser extent. I love the fact that these pieces were all crafted by hand, and I’ll continue to admire them in portraits, and search them out in some of my favorite antique shops.

Resources used include:

- http://www.beladora.com/2013/01/georgian-jewelry/

- http://www.collectorsweekly.com/fine-jewelry/georgian

- http://www.georgianjewelry.com

- http://novembersautumn.blogspot.com/2010/05/regency-era-georgian-jewelry_13.html

What a wonderful post! As a Georgian jewelry obsessive, I appreciate how succinctly you summed everything up.

LikeLike

Thanks, Taylor! I’m glad you found your way to my blog. 🙂

LikeLike

Check out this portrait for quite an assortment of different forms worn by one lady.

Gilbert Stuart, Matilda Stoughton de Jaudenes y Nebot, 1794, Metropolitan Museum of Art

LikeLike

Thanks for letting me know about the portrait, Ann! I love her dress, and I think her necklace is very cool. She certainly is wearing enough jewelry to let us know how wealthy she was. 🙂

LikeLike